Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends! We return for a third year of the Gaming Alexandria Video Game Notables: A community voted selection of historically significant games from across time and space. Our previous selections in 2022 and 2023 yielded 24 entries; this year we added 6 more to the list! Plus, two entries for a significant Non-Video Game and Person of note.

Our voting for the Video Game Notables uses the system of Ranked Choice Voting. Ever voter chooses a list of selections based on preference, which are then whittled down to the final candidates. This helps eliminate some of the strategic voting pitfalls of first-past-the-post and allows for a more diverse set of games to be considered. This time around, we had 79 entries from 16 voters in the Gaming Alexandria community. If you want to join in next year, be sure to join our Discord!

Check out the Livestream VOD where we discuss the individual entries and the trailers introducing each game! For all the inductees – check below.

2024 Inductees

Non-Video Game

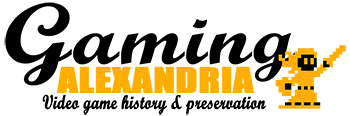

A confluence of events made Star Wars a vital piece in the story of video games. Like much great sci-fi, it was about the present of the 1970s more than the future-past it presented. It brought computer technology out of the labs, put it on screen, and made it cool. Graphical displays, robots, and space technology both reflected and ignited the world of electronics. Star Wars meant something different to nearly every community it impacted, including mainstream audiences. For video games, it provided the safety of a space setting and the freedom to bend the rules of reality for the cool factor. Its inescapable allure of a galaxy populated with the monumental and personal helped to cement American cultural dominance in a new age of art driven by computers.

The Force will be with you. Always.

Video Game Notables

A compilation for the ages. Drawn from all across the computing world, 101 BASIC Computer Games is not a game: It is a cultural artifact. A tome of type-in listings, names, and illustrations, the book is a window to a past otherwise forgotten. David Ahl’s efforts to catalog and preserve these programs made the book – and its subsequent editions – a cornerstone of the early personal computers. Star Trek, Hamurabi, Lunar Lander, Bagels: All still known today because of their presence in 101 BASIC Computer Games. From the time of the teletype to the advent of the internet, the book has always been there as a representation of some of the smallest and most significant games in computing history. The book is the essence of programming and a gateway into the computer culture of the 1960s.

Breakout tore down the walls of what basic ball-and-paddle games could be. Atari built on a legacy of Pong and its many variants to create one of the few early coin-op classics that stood the test of time. Based around the simple premise of eliminating objects on a playfield, Breakout distilled the vertical ball bouncing format down to its essence. Physical objects in a game world created the dictates of its play, without needing any elaboration. By its premise, Breakout was also one of the first truly compelling single player experiences based on competitive action. Battling against a game was rarely ever so simple, yet adrenaline inducing. Breakout is both a perfect early game-creating experiment as well as a hugely influential starting point for game designers. Abstract in its essence, yet exacting in its spirit.

Few games can match the sheer number of stylistic clones as Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord. Greenberg and Woodhead synthesized the Dungeons & Dragons experience – based on the multiplayer games from the PLATO network – creating a pure expression of dungeon-crawling adventure. A party of treasure loving strong folk dive deep into the Proving Grounds, unaware of what they may encounter in the darkness. Wizardry introduced complexity and variety on a scale rarely seen in commercial computer games. The world was varied and not static, with random encounters and puzzling mazes challenging the player’s resource management skills. Magic plays an important role in navigating the world, as does risk assessment to survive its brutal difficulty. In spite of the fact that few could (legitimately) beat the wizard Werdna, Wizardry became a template for role-playing games the world over. Once you saw its first-person corridors, it was hard to imagine interactive virtual worlds any other way.

A game shaped by a community; an adventure very few completed without it. Masanobu Endo tapped into something exceptional with The Tower of Druaga. Was it the fully realized chibi artstyle with 8-bit pixel art? Or the FM sound that defined Namco’s audio identity? Perhaps the strategic gameplay that made action out of RPG concepts? More than any of that, Druaga brought secrets to the fore of Japanese game design. Hiding crucial elements of its gameplay behind obscure rules allowed for a brimming scene of tips traders to redefine the arcade market. The synthesis of elements in its gameplay likewise pointed the way for melding the complexity of statistics-driven experiences and top down combat. Without ever making much of a tangible impact outside of Japan, Tower of Druaga nevertheless shaped the world’s experience of gaming in years to come.

We will never forgive Sid Meier… “One more turn” has turned into millions of lost hours in the depths of Civilization. Responding to the real-time strategy of SimCity, Civilization has driven the direction of games with complex systems for decades. At the center of this is the tech tree, an ingenious system of advancement which was adopted by games in all types of genres. The interface was a huge improvement over most strategy games, embracing mouse-driven selections in a way that few intricate games had enabled. How it handled turns was also very important, giving individual units their own range of actions without overwhelming players with options. Then, for some, the ability to play out and understand history from a high level was more than enough – especially with multiple paths to victory, guiding an open-ended experience. Sid Meier’s Civilization continues to compel people to because it seems endless without ever letting the player lose track. Now, just one more turn…

They’re coming for you… Inventing a genre and pioneering technology – is but one way to introduce Alone in the Dark. Its clever 3D implementation was matched by the astounding way it worked around its limitations. Pushing boundaries, Alone in the Dark brought tension to the very essence of its gameplay, crafting a horrifying experience unlike much else. The fixed camera angles allowed for players to step through two dimensional environments in a cinematic fashion. The variety and life in Alone in the Dark’s world in the context of early 90s PC gaming cannot be understated. It was an adventure game that felt like a physical reality rather than purely a series of rooms and context clues. Few games pushed the concept – and execution – of polygonal games like Alone in the Dark. All the pieces fit together in this French masterpiece of intent, which fundamentally changed the detail of video game worlds forever.

Person of Note

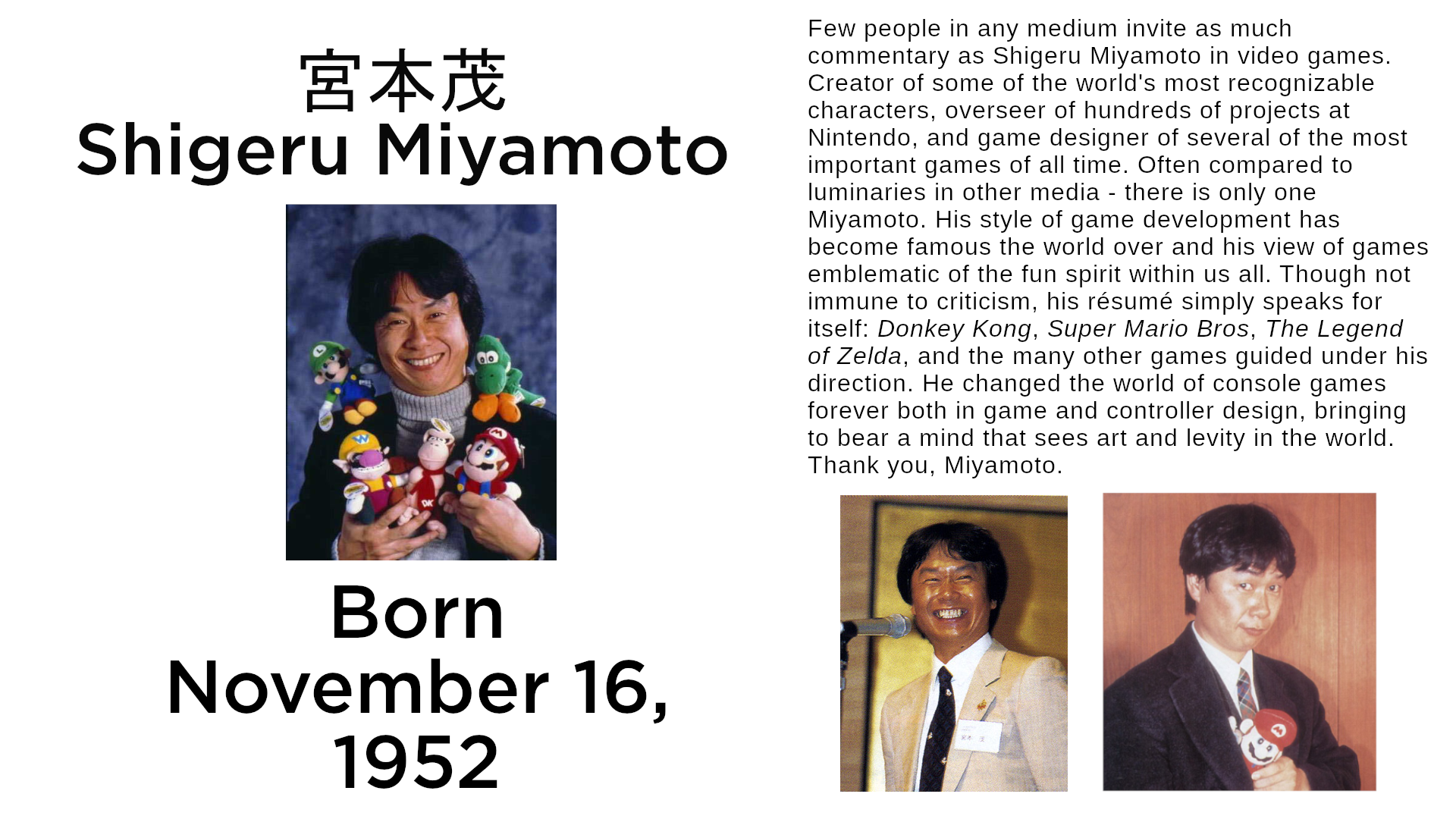

Few people in any medium invite as much commentary as Shigeru Miyamoto in video games. Creator of some of the world’s most recognizable characters, overseer of hundreds of projects at Nintendo, and game designer of several of the most important games of all time. Often compared to luminaries in other media – there is only one Miyamoto. His style of game development has become famous the world over and his view of games emblematic of the fun spirit within us all. Though not immune to criticism, his résumé simply speaks for itself: Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros, The Legend of Zelda, and the many other games guided under his direction. He changed the world of console games forever both in game and controller design, bringing to bear a mind that sees art and levity in the world. Thank you, Miyamoto.

Thanks again for another awesome year of selections! We look forward to seeing you again next year.