(This interview was originally conducted via email on December 26th, 2018. It has been edited for improved readability.)

Late last year, David Crane, the programmer best known for his work on 1982’s Pitfall! was interviewed by the Gaming Alexandria staff for input on the state of Atari in the late 1970’s. David has been working in the industry up until 2006 and left a very strong impact on the industry and it’s early days. He was also kind enough to spread information on his childhood and his interest in computing.

When did you first discover an interest in programming? How did it lead you to join Atari and become one of the earlier programmers of the 2600?

An interesting aspect of video game design to this day (although especially true in the early days), is that it is both a left-brain and right-brain activity. Since you are creating something that only takes on life if a computer system is capable of rendering it onto a display, there are a lot of technical skills required. But the most technically gifted designer won’t be able to make a fun game without a spark of creativity and the ability to recognize what it is about a game that makes it fun. Then on top of that, for a game to be widely successful it typically needs pleasing and/or realistic imagery. So it helps to be something of an artist as well.

Growing up I was very technical. I was taking apart television sets at the age of 12; engineering time- saving devices with my erector set; building a Tic-Tac-Toe computer for a science fair; and learning how to use the earliest forms of digital logic, not to mention chemistry sets and physics experiments. But I also had a natural sense of game play. Before computers and mobile games we used to play board games with our friends. Those games were often designed for a fixed number of players and it wasn’t always possible to get enough kids together to play. I was often called upon to adjust a game’s rules to allow 3 kids to play a 4-player game, etc. I learned that I had inherent understanding of fair game play.

On top of that my mother was an accomplished artist, creating in many different media, from painting in a myriad number of material genres (i.e. pen and ink, pastels, oil using brush or palette knife, watercolour, egg tempera, and others) to crafts of all sorts. She made sure that her kids were trained in arts and crafts, and as the youngest of 4 I probably got extra attention – if only to keep me occupied. But I always felt that I would do something very technical – maybe one day inventing a gadget that ended up in millions of homes.

To that end I pursued an electronic engineering degree and ultimately took a job at National Semiconductor as an entry-level engineer in one of their IC design labs, where I filled out my education with real world experience. But then Atari came along.

Through my father’s influence, I played tennis throughout my life, and I was playing tournament tennis while working at National Semiconductor. I ended up playing tournament doubles with Al Miller – who lived in the same apartment complex. One day he asked me to proofread a newspaper ad he had written for game designers at Atari that would be going into the newspaper the next day. I thought the job was a good fit for my talents, and I saw the chance to make a game (sort of a gadget) that might end up in millions of homes. I interviewed for the job the next morning; got an offer by noon; and gave notice at National that afternoon. The rest, as they say, is history.

It was as if my entire upbringing had prepared me for making video games. I had an engineer’s understanding of the hardware, an artist’s feel for imagery, and an understanding of game design. I was soon making the Atari game system perform in ways unimagined by even the system’s designers, and loving every minute of it. Sadly, the work environment at Atari deteriorated and a few of us decided to leave the company and practice our art for ourselves. Activision was born.

Since those days I have published nearly 100 products (counting only those games that were either primarily my design or my programming), on more than 20 game systems using more than 20 programming languages. Pitfall, considered by many to be my seminal work, recently still made the list of the 100 greatest games of all time – despite the hundreds of thousands of games created in the intervening years. So I guess it was a good career choice.

What was the earlier development hardware for the 2600 like?

At both Atari and Activision, a small, custom 6502 computer was engineered to serve as a development system. This 6502 computer, made with commercially-available parts, had an umbilical to plug into the 2600’s cartridge slot. I engineered and manufactured Activision’s unit, housed in a blue sheet metal enclosure, that was affectionately referred to as a “blue box.”

The umbilical allowed the hardware inside the 2600 to reside in the memory space of the blue box, which in turn contained ROM and RAM in memory blocks unused by the 2600. With that arrangement we could load game program data into RAM such that it looked like ROM to the 2600. Code in the blue box was configured to boot-load game programs, as well as allow the game programmer to read and/or modify memory locations manually, set program flow breakpoints, etc.

Each blue box was connected through RS-232 to a PDP-11 computer. Programs were authored on the PDP-11 using rudimentary text editor programs. Edited source code was then assembled (i.e. compiled) into 6502 machine code on the PDP-11 and then downloaded to the blue box. We could then play test each new feature as we coded it directly on the 2600 hardware. A typical day was a series of loops of editing, downloading, play testing, then back to editing.

The power of the PDP-11 computers improved exponentially over time, but the first computer we used at Activision took 20 minutes to assemble a 2K game, and 40 minutes to assemble a 4K game. That computer was also not capable of time-sharing, so while it was assembling Larry Kaplan’s 4K Bridge game, for example, nobody else could edit or assemble – unable to do anything but play test – for 40 minutes. Fortunately by the mid-1980s we had upgraded to a multi-tasking system that could support everyone working simultaneously.

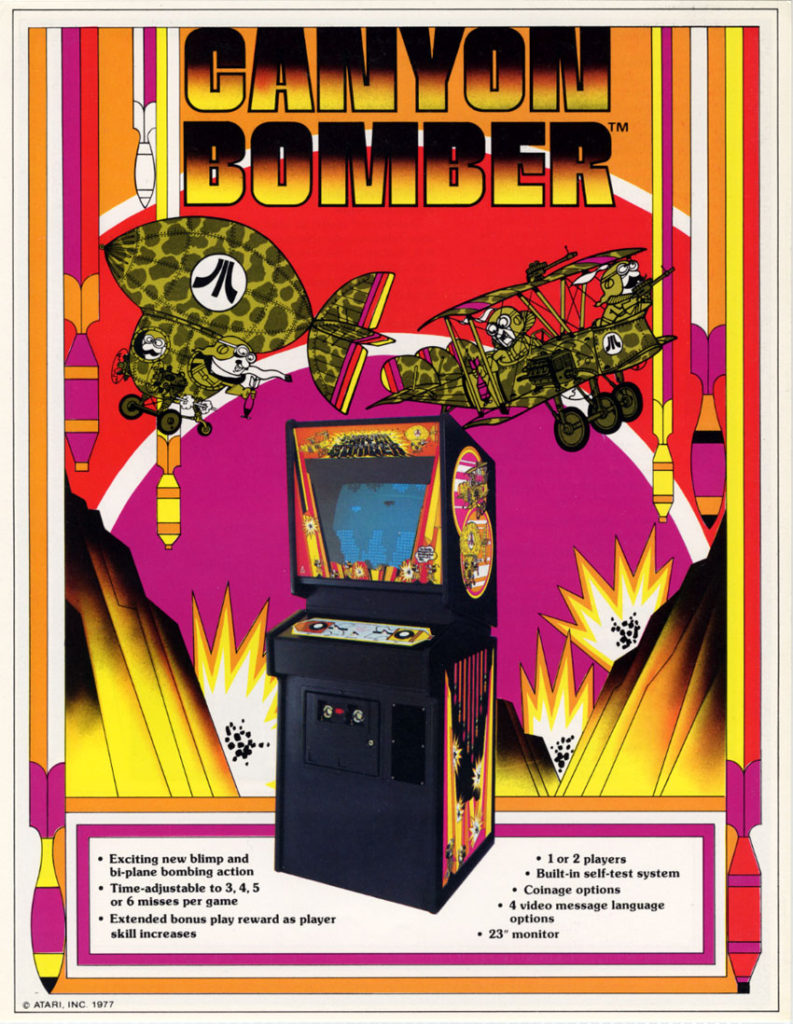

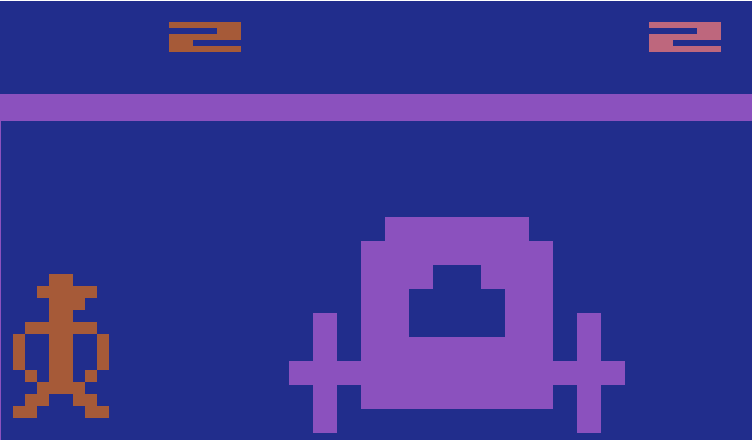

What was the process of porting early Atari Coin-ups such as Outlaw and Canyon Bomber to the 2600? Did you have any involvement with the arcades originals?

It was one of Atari’s goals in creating the 2600 to allow people to play home versions of their arcade classics. That is why the hardware was designed with games like Pong and Tank in mind. But an arcade game machine cost several thousands of dollars, and had 100 times the hardware capability of the lowly 2600. So making a home version of an arcade game was never easy, and sometimes impossible.

The good news is that Atari management, at least at the game development level, understood that 2600 game designers / programmers were the only people who really knew what the 2600 was capable of doing. So rather than telling us to make a particular game – which might not even resemble the original – they just encouraged us to play the games in the company arcade and explore possible ways to implement them.

I made one 2600 cartridge that played a version of two of Atari’s arcade games: Canyon Bomber, and Depth Charge. I was able to do that because I could envision how to use the 2600 hardware in such a way as to make a game display with similar components to the arcade game.

I was never involved in any of the arcade games in development – that happened in a separate facility. We saw them only after they were complete.

One thought on “The Blue Box: David Crane On Early Atari”