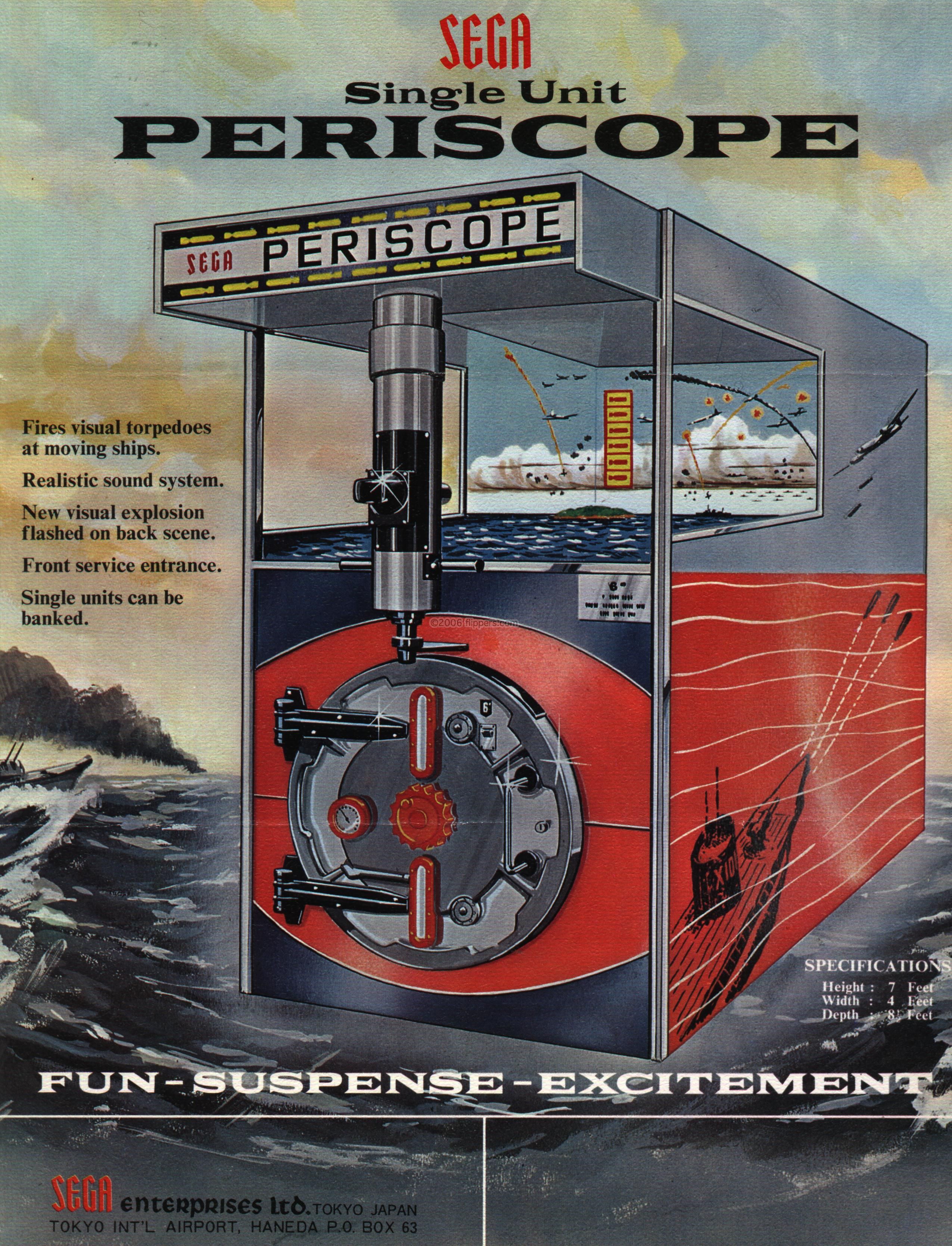

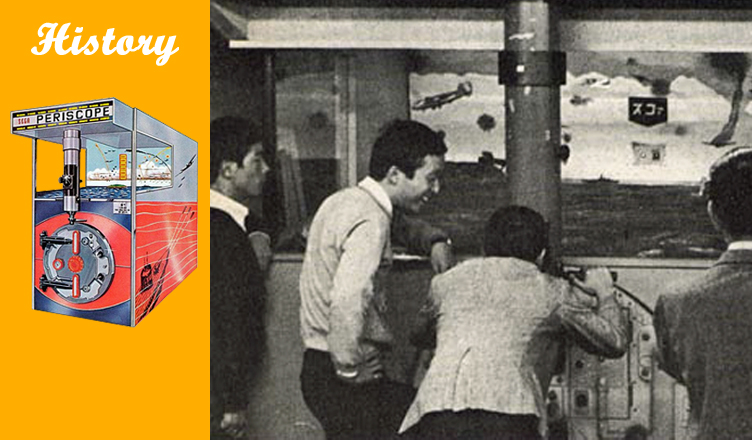

Periscope (ペリスコープ) was an electro-mechanical game released in multiple international markets in the mid-to-late 1960’s. In the game, a player is tasked with aligning their viewport – stylized as a submarine periscope – with ship targets on the other side of a Plexiglas sea. When a player pushes a button attached to the periscope, a mortar is sent flying, represented by a lit object travelling across the play area to the other side. When it hits either the sea or a ship, a sound of destruction is heard, and if the latter occurs there is an extra visual effect of an explosion in the distance to indicate the ship is sunk.

This game was revolutionary for a number of different reasons, both in its presentation as well as helping to standardize a quarter per-play in the United States, but the question of who can claim credit for developing the game is a mystery which we still do not know the answer to.

The two primary candidates for the creation of the game are Japanese amusement companies Sega Enterprises Ltd. and Nakamura Seisakusho Co Ltd. (later Namco). Both companies have the game listed in their official product timelines with Sega listing Periscope as being released in 1966 and Namco listing the game as 1965. No official acknowledgment of the other company’s claim has been spoken of as of this date, therefore we are left with conflicting and largely unsupported accounts of the timeline and ownership.

In this post we will be examining the various claims and sources which support the numerous sides to this story. Nothing conclusive has yet been found which definitively gives credit to one company or another. While Sega is currently in the history books with its own claims, it is worth acknowledging all the available evidence in order to draw some better substantiated conclusions.

Nakamura Seisakusho Co Ltd. (中村雅哉)

Nakamura Seisakusho (translated as Nakamura Manufacturing), founded by Masaya Nakamura, began as an operator of rooftop amusement spaces in 1955. The founder’s engineering background led them into creating custom amusement spaces starting in 1963 with the Mistukoshi department store in an attraction called Roadway Ride. Having moved into the custom manufacturing of rides for several other Mitsukoshi rooftop spaces, Nakamura Seisakusho decided to become a general manufacturer of amusements, starting with kiddie rides with various licenses such as Walt Disney animations (Baba 1993, pg 150-151; Smith). According to Namco’s historical game listing, they began to build these first machines in 1965.

Also in 1965 is when the Nakamura version of Periscope was supposedly built. There is no evidence from that time period that has yet surfaced which confirms this release date. It is unlikely that trade publications for coin-operated games in Japan were very widespread at the time, if they existed. The closest coin-op publication to the 1960s known to exist is the 1969 Yumio Machine Directory (which does list both Periscopes, but gives no indication as to their year of release).

The only somewhat contemporaneous source available in English is a picture and small article in the April 15th, 1967 issue of Cash Box which warrants the Nakamura’s first known mention in any English source. The unit is designated at NP-3D and Masaya Nakamura says he will give special attention to those looking to import the game from elsewhere in the world. This confirms at least that one version of Periscope existed by that time, one which visually appears slightly different to Sega’s own model. It also strongly implies that no exports outside of Japan had, at that point, been undertaken.

Following that mention, in the January 1977 issue of Play Meter, Masaya Nakamura was interviewed by editor Ralph Lally. Here is the transcript that relates to Periscope:

Play Meter: What was the first amusement device that you built?

Nakamura: It was a submarine game, called Periscope, a three-player game, three periscopes set up in parallel.

PM: And what was the next step from there?

N: Then we made a tank game adapted from a big tank battle between the Allied forces and German forces during the second world war.

PM: When you started manufacturing, did you sell these games to your competitors, the operators you had been distributing to?

N: Yes.

PM: The submarine game that you mentioned sounds like Seawolf, yet this was ten years ago: would that be the first periscope game ever?

N: I don’t believe so, but it was the first famous submarine game in Japan. I think there were some similar games before. However this was the first famous periscope game. (Lally 1977)

The game historian Alex Smith of They Create Worlds has reckoned that being described as the first ‘famous’ submarine game relates to Sega’s international success with Periscope, which does not appear to have been from Namco itself. As mentioned, any sort of evidence of a deal between Namco and Sega for this game has not yet appeared beyond speculation. Alex does make the point though that members of Kasco, another Japanese coin-op manufacturer, stated in a retrospective interview (available in English at the website Shmuplations) that Sega was a major outlet for international releases of games. It does not appear that Kasco ever went through Sega to export their products, but they also did not release many games stateside at all.

The next piece of evidence is a flyer which can be seen on the Namconian blog and in an enlarged version in this Youtube video. The logo at the bottom of the flyer, written in Kanji, does read ‘Nakamura Seiaskusho Co. Ltd.’ along with their horse mascot at the time. However, the poster does not contain any sort of date. The Youtube video states that in the Japanese strategy guide for the Namco game Time Crisis 2, a timeline of Namco shooting games states that Periscope was a 1965 game.

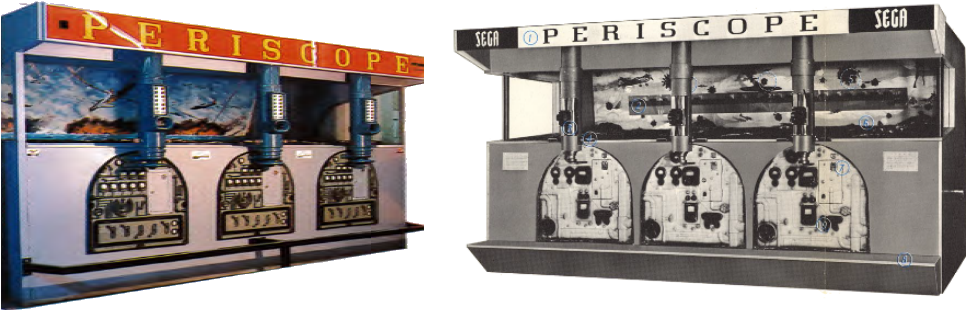

Several photos of the Namco Periscope have appeared over the years. The first one widely distributed was featured originally in the Yumio Machine Directory from 1969, then reprinted in the promotional book Namco Museum 1955 to 1982 (courtesy of @onionsoftware on Twitter) from 1982, showcasing a black and white frontal photo of the machine from the flyer, noted with a date of 1965. A color photo appeared in the follow-up booklet, Namco Museum 1955 to 1984: All the Namco Goods in 1984, however this time the date was made ambiguous in the 1965-1966 timeframe. The image as it appears in the book has a removed background, which was kept for it’s appearance in the arcade history tome それは「ポン」から始まった-アーケードTVゲームの成り立ち (In the Beginning, There Was Pong) by Masumi Akagi.

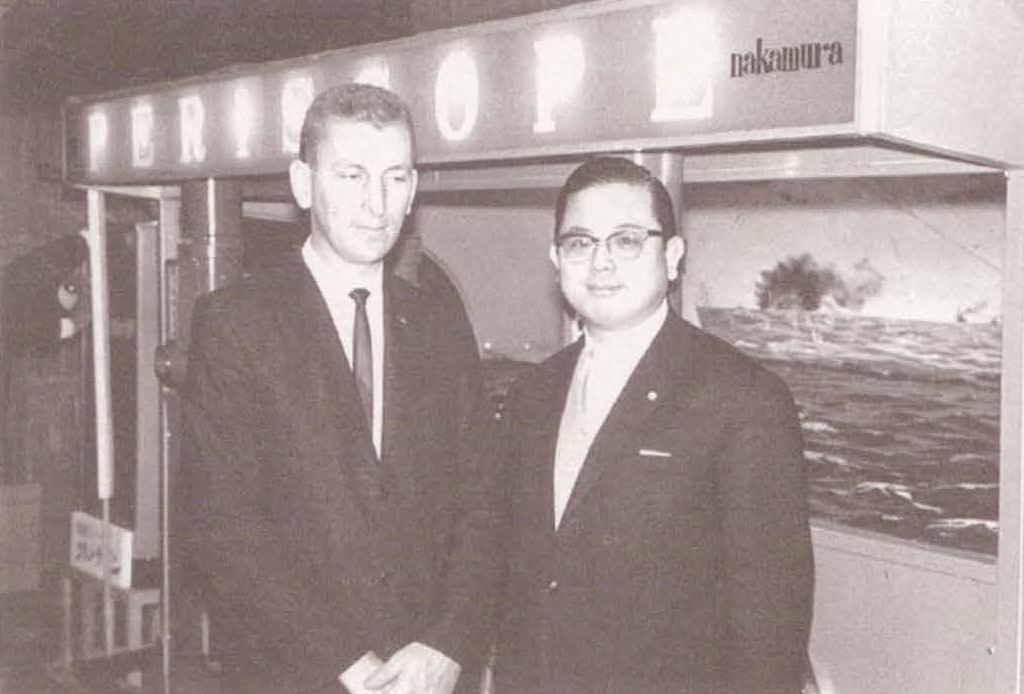

A third photo appears in the book ギャラクシアン創世記 -澤野和則 (Galaxian Genesis – Kazunori Sawano) by Zeku (aka Twitter user @Area51_zek) which features Masaya Nakamura standing with an unidentified man in front of a Periscope unit, dated as 1965. The source of this photo is as yet unknown.

In this Twitter exchange between @onionsoftware and @area51_zek regarding the second photo, the latter user states some information about this unit, presumably from the research on Namco which went into the Galaxian Genesis book. He states that the product was originally known as 魚雷発射機 which in Kanji translates as “Torpedo Launcher” before later being called Periscope. This is supported by the reproduced image of the game appearing in Akagi (2015, page 51) with the same label. However, Zeku points out an inherent contradiction in the book. When discussing the Nakamura Periscope, author Akagi says something to the effect of the design being different than that of Sega’s Periscope (which is described in an earlier chapter), yet he lists the Nakamura game as 1965 and the Sega game as 1966 (Akagi 2015, pg 43, 50).

These pieces of evidence have led Alex Smith to posit that perhaps Periscope originated as a custom rooftop installation model, similar to Nakamura Seisakusho’s Roadway Ride. The company had just started to become a manufacturer in 1965 and did not have a full-scale factory in Tokyo until February of 1966 (Akagi 2015, page 50). It would make sense if Nakamura made the first model in 1965 for a specific venue and then was not able to go into larger production until 1966 or 1967, which is when Cash Box first noticed it.

Periscope is also mentioned in connection with Masaya Nakamura in the seventh issue of a gaming publication called AM Life in 1983, though with no further detail. The JAMMA website also prints the second Namco Museum picture with a note of the game being from 1965 and the Sega version being 1966.

This is the current extent of resources know to exist in relation to Nakamura Seisakusho Co Ltd. and Periscope. The fact that the Nakamura Periscope is very sparsely covered could have as much to do with the company’s size at the time as much as its relationship to Sega’s unit. It is very logical to draw the conclusion that when Masaya Nakamura relates Periscope as being Japan’s first ‘famous’ submarine game, he likely wasn’t referring to the original model that his company created. However, let’s not discount the evidence that Sega may have originated the concept, as their side of the story is better documented, even if many of the pieces of evidence contradict themselves.

Sega Enterprises Ltd. ( セガ・エンタープライゼス)

Sega was fully formed as a company in July of 1965 through the merger of the companies Nihon Goraku Bussan and Rosen Enterprises Ltd, quickly becoming Japan’s largest coin-op amusement company. At the time, neither of the merged companies was a true manufacturer of amusement equipment. The Nihon Goraku Bussan side made jukeboxes (like the famous Sega 1000), slot machines, and probably made at least one game beforehand but for the most part they both imported product from the United States (primarily target shooting games) (Smith).

At the impetus of the new Sega President David Rosen, Sega decided to move in the direction of becoming a major manufacturer of games (as well as remaining big in jukeboxes) (Smith). They had a factory and started to build up a technical and R&D staff around this time. One source (Oshita 1992, pg 104) claims their very first game R&D effort was the game Basketball, but they quickly moved onto more advanced electro-mechanical games.

The first mention of Sega’s Periscope comes out of a London based trade show called the ATE which opened on November 28, 1966. It is important to point out that Cash Box has the description of “the Sega Version of the Torpedo Shoot Periscope game”. “Torpedo Shoot” is actually a different game which will be discussed in the third section of this article, and the claim of it being a version of a previously existing game will also be discussed.

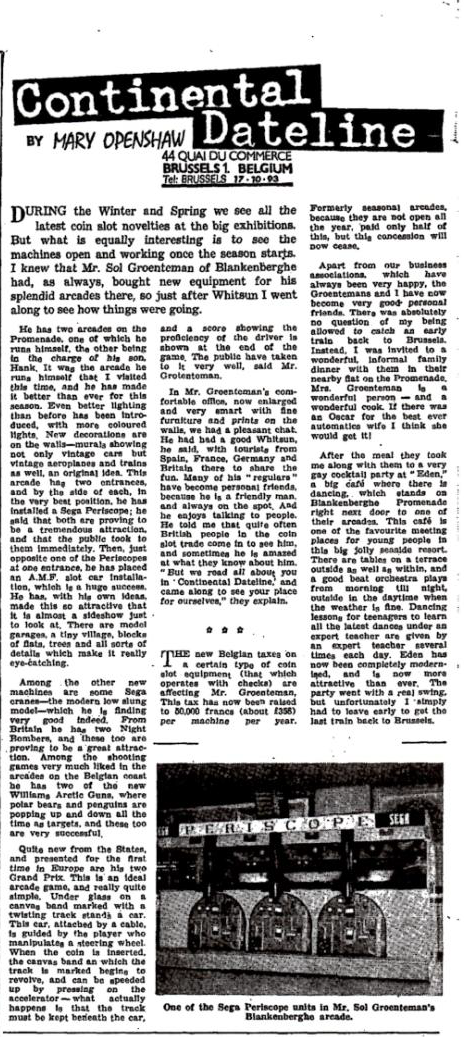

The first known photo of the Sega Periscope game appears in a European coin-op publication called Coin Slot in the June 24, 1967 issue. The article speaks about an installation of the game in a Belgian arcade (some of the information is reprinted more legibly in the July 27, 1968 issue of Cash Box). Freddy Bailey, the excellent European coin-op historian who provided this information, says that Marty Bromley of Sega Enterprises Ltd. was a partner in this particular arcade, and that the owner Hank Grant told Bailey that the unit was first installed in April of 1967.

Subsequently, the Sega Model was shown at the Hotel Equipment Exhbition in Paris starting on October 12, 1967 at the booth of distributor Socodimex. This would be the last seen of the model in English language publications until they decided to take the machine stateside.

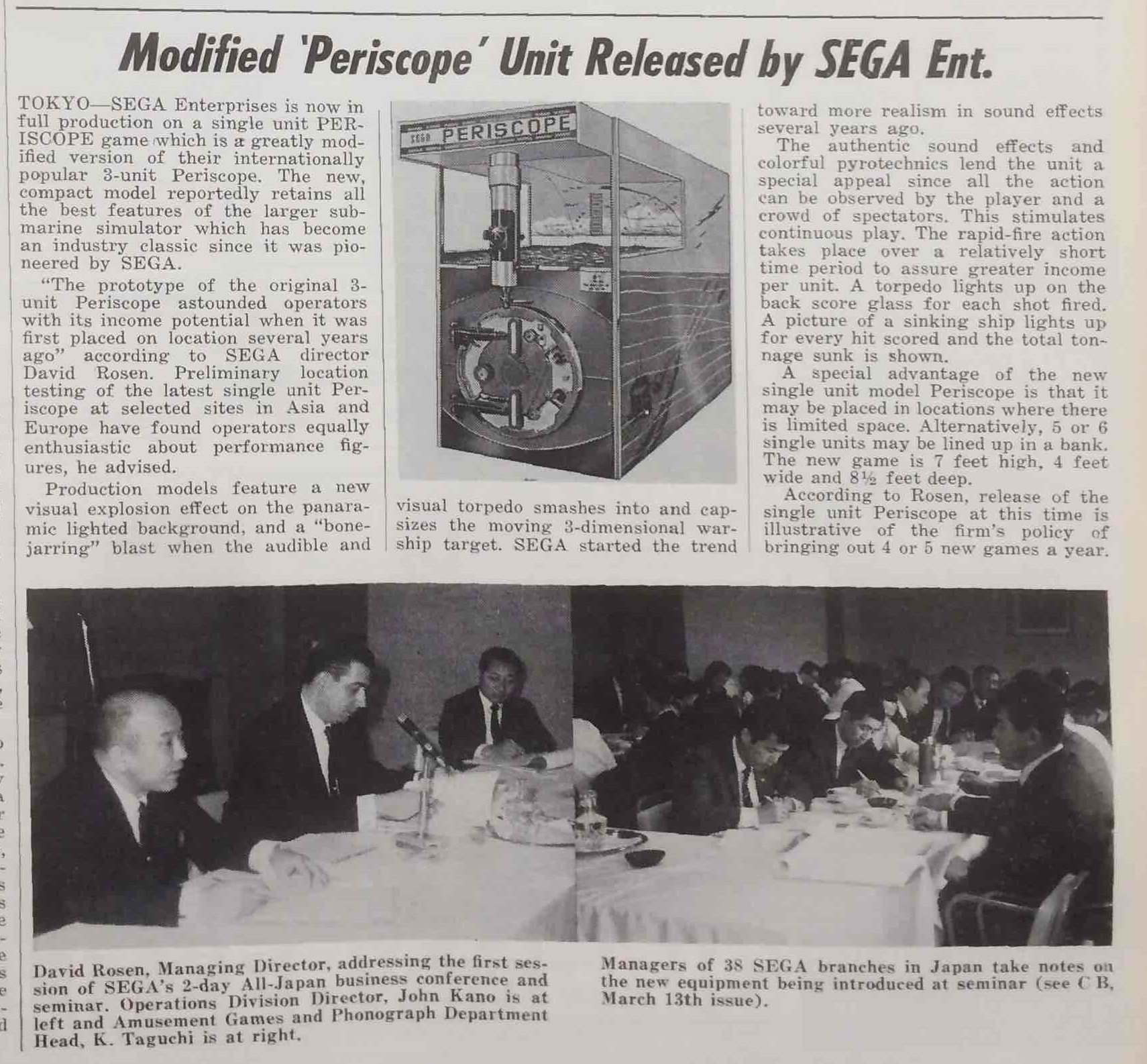

The launch announcement for Sega’s Periscope in the March 23, 1968 issue of Cash Box is packed with interesting info for both this specific game and the company as a whole. What is made clear through this piece is that Periscope is continually referred to as a game with some age. Cash Box refers to it as “an industry classic” and David Rosen says the original game “was first placed on location several years ago”. For the American market, the design has changed to a model which houses only one set of controls, probably to minimize the cost of exporting (Sega did not yet have an American manufacturing operation at this time).

So all of this establishes that Sega’s Periscope definitely existed in 1966 and that it first came to the American market in March 1968 in a single unit variant. Since almost every reliable dating of the game states an initial release year of 1966, there is no need to go back over that with subsequent claims as with Namco. Instead we’ll look at the circumstances behind the game’s creation, which is reported differently in almost every Japanese source.

The earliest version of this story comes from Oshita (1992). The author claims that Sega’s original game creation was largely based on American games, including Basketball, and that Periscope was supposed to be a directive for creating original content at the company. The head of this initiative – and the project – was an engineer named Ochi Shikanosuke (whose name appears in a number of very important Sega patents). They finished work in Spring of 1966, but it’s unclear if the game was released in Japan. (Oshita 1992, page 104)

The book goes on to describe the game being showcased at the 1967 “ATA” show (probably the 1966 ATE show) in London, where the assembled distributors started playing the game with great enthusiasm whilst Ochi was repairing it (he being on hand in case there were any issues). All assembled were very impressed with the audio-visual magic on display, which was rare if not totally unseen in the coin-op world at the time (Oshita 1992, pg 104-106).

The next mention is from Akagi (1993), where the subject of popular submarine media is placed a backdrop to the reason behind the game’s creation. Specifically the manga series Submarine 707 which began publication in 1963 (though the author erroneously mentions both Hunt for Red October and Silent Service as highly tangential, popular submarine movies from much later) (Akagi 1993, pg 35-36).

Finally, the story which has somewhat leaked to the English speaking world appears in Akagi (2015). In this telling, David Rosen sketched out the design for Periscope personally and it was built in 1966 (Akagi 2015, pg 43). Later in the book, it is mentioned that Ochi Shikanosuke had been the head of Sega’s development efforts since Periscope (Akagi 2015, pg 143). As mentioned in the prior section, it is claimed that Nakamura’s Periscope was unrelated to this one, ‘different’ is the translated word.

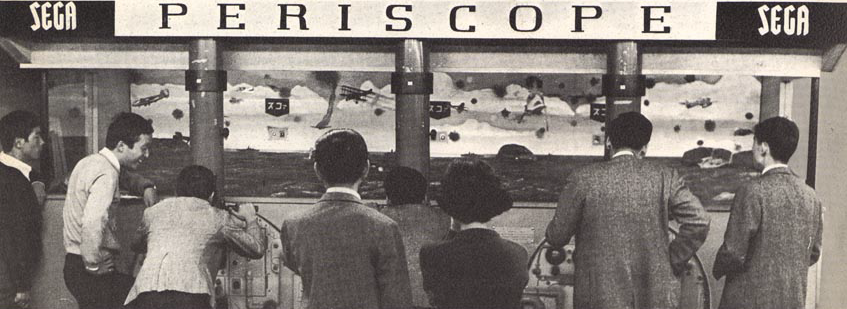

Let’s speak about differences in the design of the two versions. The clip above is the only known footage of a Sega single unit Periscope machine in action, and it is very brief. Only one known surviving unit of Periscope has been seen on the internet, but it was last heard from over a decade ago. Sega themselves included a simulation of the single model Periscope on the Playstation 2 release Sega Ages 2500 Series Vol. 26: Dynamite Deka which could be played for extra lives. A clearer visual of the three player version can also be observed in good detail in a brochure posted on Sega Retro. Unfortunately for the Nakamura model the pictures aren’t as pristine, but give us enough of an overview to speak about some outward aesthetic changes.

We can assume that functionally, if not mechanically, the Periscope models are the same. All indications point to the same sort of gameplay being in both versions, if not all the features. The most noticeable difference that can be seen in the façade of the Nakamura version – and not so much in the Sega version – are the visible rivets right above the viewport. Right below the periscope itself, the panels which adorn the front are quite different, though both are housed within the same general shape. The backglass environment is clearly different between the two, though both show planes and warships on fire over an ocean. The Sega version has white rectangles on the outer edges (which are presumably instructions) and the Nakamura version has them in between each of the Periscopes. Lastly is the marquee, where Sega’s logo takes up both sides of the top whereas the Namakura logo is limited to the right side. The font for each is suspiciously similar, but the Sega version has it’s serifs squared off (like proto pixel art!).

So are these versions really ‘different’ to each other in any substantial way? It is likely that Akagi (2015) was attempting to hastily explain away a contradiction which wasn’t at the center of his research, since none of his sources in the back of the book seem to indicate that he knew the Nakamura side of the story very well. @onionsoftware corresponded with Masumi Akagi on the matter, and said that he was uncertain about the game’s origins, believing that it may have even been based on an American game.

So before we rest the debate on the two Japanese companies’ merits, there is actually a third side to this story. We will also be clearing up some misconceptions about some similar, but unrelated games.

Mayfield Electronics Ltd. and Nixsales Ltd.?

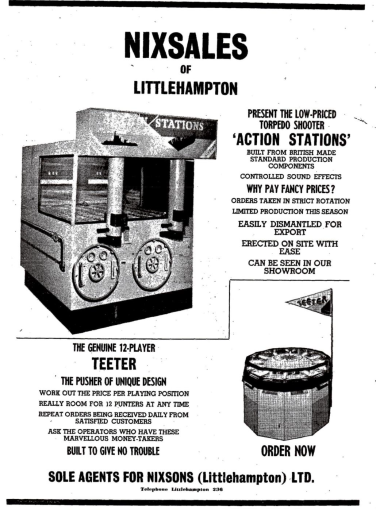

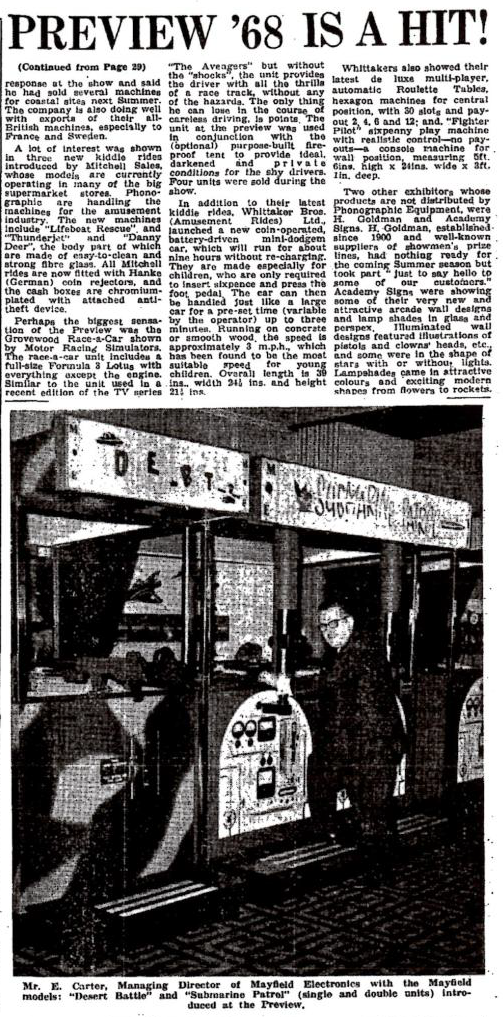

There is not a lot of background on either of these companies, as information available outside of Europe is very limited. Mayfield Electronics Ltd. (also affiliated with a company called Mayfield Automatics) was a Lancashire, England based manufacturer of a wide variety of coin-operated equipment including slot machines, puppet shows, and forty person slot car race tracks. The company draws its first mention in Cash Box in August 1964 and closed in 1972. Nixsales Ltd. (also known as Nixson) was from Sussex, England and may have manufactured a coin pusher machine around 1967.

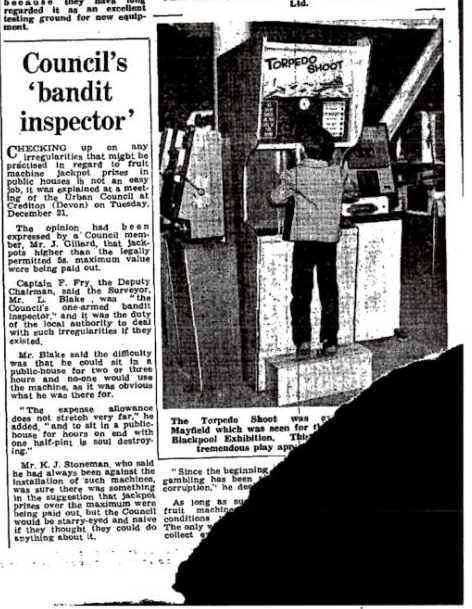

In about 1965, Mayfield introduced a game called “Torpedo Shoot” to the British market. This game was not the same as Nakamura’s or Sega’s Periscope, though it was had some similar characteristics including sound effects. Instead it was a self-contained target shooting game of the like which were very popular in the 1960s where players shot missiles in the dark. This game was probably an evolution of a 1940s shooting unit by Bally called Undersea Raider, sometimes referred to in the coin-op publications as Periscope, which features superficially similar target shooting gameplay. Taito – under their Crown label – also had the same kind of game and called it Periscope, but all of these games have (seemingly) nothing to do with the Periscope we’re speaking about.

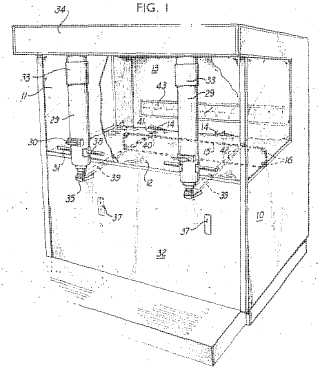

Mayfield Electronics had a possible relationship with Sega, as Sega was in the British slot machine business in the 1960s before exiting that market entirely. A Sega patent from 1994 actually references a Mayfield patent (though it does not relate to Periscope). However, on December 16, 1966 Mayfield Electronics filed for a patent (with a priority of the same date) for “A New or improved Indoor Game Apparatus” by inventor Edward Oswald Carter. Viewing the patent drawings, it is very clear to see that the machine is extremely similar to Periscope, but in a two-player version rather than three or one.

Sega along with the both of the two British companies are referenced in the February 11, 1967 issue of Cash Box regarding the upcoming Northern Amusement Equipment and Coin Operated Machine Exhbition in Blackpool, England which opens on the 27th of that month. Directly comparing Sega’s machine (though still calling it ‘Torpedo Shoot’) both Mayfield Electronics and Nixsales are said to have new models available at the show, fitting in well with Mayfield’s patent date.

The first visual appearance of these two player models comes from Nixsales Ltd. on March 4, 1967 in the British coin-op publication Coin Slot labelled as the “Action Stations”. Viewing the ad shows a possibly cheaper version of the Periscope game; definitely too wide across to be a traditional shooting game set-up like Undersea Raider but not deep enough to have the same depth-of-field effect as the real Periscope.

Mayfield Electronics’ version, called Submarine Patrol, appears in the November 11, 1967 issue of Coin Slot where it is stated to have been previewed by Mayfield’s Managing Director E. Carter (presumably the Edward Oswald Carter who patented it).

So what does this all say? Well, the most interesting part of this whole affair is that Mayfield actually patented the Periscope-alike in a reduced form-factor., and did so mere weeks after the ATE show where Sega first showed Periscope in Europe. As far as anyone’s aware, neither Sega nor Nakamura ever patented anything in regards to Periscope, or seemingly left any paper behind in regards to their development.

While the obvious conclusion to draw from this is that Mayfield Electronics stole and patented Sega’s work after viewing it at the ATE show, it is at least possible that Mayfield were the originators of the concept and were soured on a deal with Sega. After all, if Nakamura Seisakusho is never mentioned in connection with Sega, Mayfield could just as well be in their position. However, this is unlikely. The Japanese industry was very insulated from the worldwide stage and an effective collaboration would have been logistically difficult between these two companies. Plus, Sega proved themselves imminently capable of following up on Periscope technologically, whereas Mayfield was relegated to the dust bin of history.

Conclusion

What to say about the authorship of Periscope then? The game has a legendary status in the coin-operated games industry in many corners of the world. Figuring out the authorship with help increase our understanding of the companies involved and how this game came to be as big as it is. Lacking that information has given us some avenues to understand the late 60’s coin-op industry better, but provides more questions as we speculate the origins of this machine.

In the opinion of Alex Smith, he believes that the machine originated at Nakamura Seisakusho, that Sega copied the machine without authorization, and then these British manufacturers ripped-off Sega. His reasoning behind this chain of events is that Sega likely didn’t have the engineering expertise to build a machine like Periscope from scratch, whereas Masaya Nakamura at Namco had some engineering background and was proven in later years to hire some of Japan’s greatest technologists for his games (Zeku).

There’s no indication of Sega licensing the machine, and in fact if it was licensed why would Masaya Nakamura be offering direct import assistance in the April 15th, 1967 issue of Cash Box? If he already had a partnership with Sega, who was already showing the game in Europe, there would theoretically be no need to solicit importers from the United States. It is pertinent to note though that the Japanese market on a domestic level – at least in the era of video games – often involved smaller manufacturers licensing their product to be built by others with larger capacities, sometimes even multiple companies (as in the case of Space Invaders and Galaxian). It is possible that a non-exclusive deal was signed, but that would be pure speculation.

One last point that Alex notes is that the majority of material for Sega’s three-player Periscope appears to be directed at the English-speaking audience, including the brochure. While the Yumio Machine Directory in 1969 gives specifications for the original Sega machine, there’s no direct implication that it is on sale in Japan. The three-controller model may have been created specifically as a product for export to foreign markets (though highly impractically, which is supposedly why it was scaled down for the American release).

Believing that Sega created the initial model creates the least contradictions in the story based on other sources. After all, Masaya Nakamura only claimed that Periscope was the first game – not the first original game – that his company created. This would conflict with dates provided by both of the companies however, plus it would portray the smaller company in a poorer light (not that it was at all uncommon for arcade game companies to make rip-offs to get off the ground).

It is entirely possible that the original “Torpedo Launcher” game was created as a custom amusement attraction, similar in concept (though not in scale) to Nakamura Seisakusho’s original Roadway Ride. Scouting out the competition, David Rosen could well have sketched out a design for a similar game based on his experiences viewing this machine, knowing he would be able to manufacture it better than this small company. Shikanosuke Ochi was made the head of the project, seeing the design through to it’s creation while Sega explored using their astounding new technology to break into international markets, ones that could more reliably house very large cabinets (which were not very prevalent in Japan until Periscope hit big) (Zeku). There is some kind of broken link in this chain we currently know nothing about.

All readers are invited to come to their own conclusions based on the sources available. Hopefully this was a comprehensive (and not too convoluted!) view of the ordeal. Any questions can be asked below or sent to the author.

(This article was posted in it’s original form to The History of How We Play blog on June 16, 2017. It has been updated from the original for clarity and to add new information not available at the time of the original post.)

Thanks:

Alex Smith for endlessly fascinating conversations and historical insight.

Freddy Bailey for all of the European coin-op information.

Keith Smith for great source compilation and background on these coin-op companies.

武田さん for providing insight and answering my questions.

Sources:

Akagi, Teppei (赤木哲平). セガvs.任天堂 : マルチメディア・ウォーズのゆくえ. 1993.

Akagi, Masumi (赤木真澄). それは「ポン」から始まった-アーケードTVゲームの成り立ち. 2015.

Baba, Hironao (馬場宏尚). セガに怯える任天堂. 1993.

Lally, Ralph. Play Meter. January 1977.

Smith, Alex. A Technological Revolution. 2015.

Zeku (ぜくう). ギャラクシアン創世記 -澤野和則. 2017.

your mention of Eddie Carter with a version of Periscope raises some interesting thoughts, as his son Alan’s company Alca had a career of making sega derivatives – first unofficial, a la Super Missile in ’69, and then officially through Marty Bromley and Michael Green; further details are found in Alan Meade’s Arcade Britannia. That said, the earlier Periscope doesn’t quite factor into this partnership, and Mayfield’s machines at the time would be seen as being in competition with Sega’s machines, distributed in the UK exclusively through Phonographic since ’61 (though Freddie Bailey’s parents showcased Berlin-made sega fruit machines there prior) and both Eddie and Alan have a bunch of innovative machines to their names as well, so its hard to discount their possible origination of it.

Periscope comes up a few times in another article of yours on Rosen, where in discussing 25c play, he mentions that motopolo, helicopter, and periscope were all developed in succession and designed around the quarter; Sega Retro cites a 1968 release for the former two (and for periscope in the US). In his speech in ’82 Rosen mentioned Periscope brought quarter play to the US in 1966. It’s very possible the three machines were released out of order, with Periscope chosen as the flagship; Sega Retro’s sources on periscope’s US date both come from a single issue of Cash Box some years after the fact.

Another point that may be worth mention, in her speech for her father’s induction into the AAMA hall of fame, Lauran Bromley states that Marty was behind the push for quarter play.